At last a post with a Craig Rudy-esque title.

Megan has asked me several times for a list of the films that the stills which run down the right side of this page are taken from. Here they are along with some links about the films and their directors.

The first two stills are from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film, le Mepris (Contempt): Brigitte Bardot standing on the roof of Casa Malaparte in Capri and Jack Palance throwing a film can discus-style.

The next two are from Rainer Werner Fassbinder's 1981 film, Lola (two shots of the actress Barbara Sukowa).

Next are series of stills from three other Fassbinder films: (Angst essen Seele auf, 1974) Fox and His Friends (Faustrecht der Freiheit, 1975) and The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (Die Bitteren Tranen der Petra von Kant, 1972). The first two stills feature Fassbinder himself as an actor.

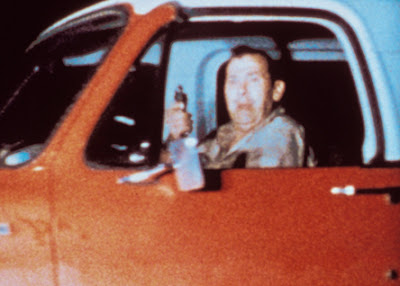

Stills from three more Godard films are next: Alphaville (Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution, 1965), Weekend, 1967 and Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live, 1962).

Don't Look Now, Nicolas Roeg, 1973.

The Case of the Grinning Cat (Chat perches), Chris Marker, 2004.

Cremaster 3, Matthew Barney, 2002.

Two stills from Paris, Texas, Wim Wenders, 1984.

Baise-moi, Virginie Despentes, 2000.

Pandora's Box (Die Buchse der Pandora), G. W. Pabst , 1929.

Distant Voices/Still Lives, Terence Davies, 1988.

Trust, Hal Hartley, 1990.

So Close (Chik yeung tin si), Corey Yuen, 2002.

M, Fritz Lang, 1931.

Dancer in the Dark, Lars von Trier, 2000.

I Walked With A Zombie, Jacques Tourneur, 1943.

My Neighbor Totoro (Tonari no Totoro), Hayao Miyazaki, 1988.

Sunset Blvd., Billy Wilder, 1950.

Fire Walk With Me, David Lynch, 1992.

Night of the Hunter, Charles Laughton, 1955.

Suspiria, Dario Argento, 1977.

Nosferatu (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens), F.W. Murnau, 1922.

Street of Crocodiles, Quay Brothers, 1985.

Bad Timing, Nicolas Roeg, 1980.

Forty Shades of Blue, Ira Sachs, 2005. (Not a great film, the still was chosen purely for a representation of the great actor, Rip Torn).

I've tried to provide a broad variety of websites and resources in my links for both films and their directors. But there is one online film journal I've cited over and over: Senses of Cinema. Simply put, I think its the best online film resource period. Their coverage of film history, particular directors and important issues in cinema is very impressive and I've always found every essay and entry to be thought full and well-written. If you're interested in reading more about film, its a great place to start and if you're interested in pursuing more film studies, I also recommend it as valuable research resource.

Tuesday, May 8, 2007

Thursday, May 3, 2007

Lil' Red in da hood...

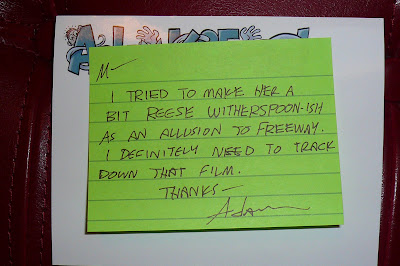

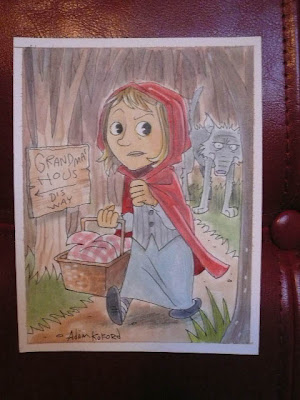

Adam Koford is a cool graphic artist who sometimes draws under the name Ape Lad. I've seen his work here and there, and was particularly chuffed to see him offering original artworks for $20 a pop. He'd been contributing to a pan-internet Flikr collaborative project "700 Hoboes" which has spun off into 700 many other categories of things.

He was offering to custom draw anyone's favorite fairy tale, and if you look on his blog to see examples, you can see that he's now moved on to doing monkey drawings for hire.

Let's hear three cheers for Ape Lad!

Sunday, April 29, 2007

The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood

The title of my post comes from folklore scholar Jack Zipes's study of the "Red Riding Hood" tale. His book along with the more recent work of Catherine Orenstein, Little Red Hiding Hood Uncloaked: Sex, Morality and the Evolution of a Fairytale, present a fascinating look at the narrative's historical development and demonstrate the way that what originated as a coming-of-age folk tale celebrating young women's wisdom and survival skills was transformed into a blame-the-victim patriarchal morality tale.

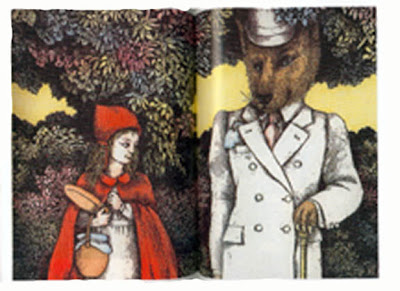

That this "innocent" children's story is a coded lesson on sexuality is made obvious by looking at the illustrations that have accompanied the myriad re-tellings and versions of the story. For every realistic (yet talking!) wolf, there are an equal number of pictures like those in the gallery above which not only pose Mr. Wolf on two legs, but dress him in, often suave and stylish, human clothes. The big bad wolf is clearly a man, baby!

As Zipes writes, the "little red" narrative had its beginning in the oral folk traditions of Europe. Folklorists note its links to several common forms of folk tales: warning tales, problem-solving tales, and coming-of-age stories. The first two featured child protagonists who negotiate or overcome some difficulty. These taught children specific lessons about safety as well as demonstrating that children could successfully look after themselves. The third kind, the coming-of-age story celebrated the adult male and female roles children would eventually assume. They allude symbolically to adult occupations and employ narratives structured around the replacement of an old person by a younger one.

Folklorists have recreated the oral tale that gave rise to "Little Red Riding Hood." "The Story of the Grandmother" retains a recognizable outline, but with some significant differences. In the ur-version the girl is not disobedient but merely curious. She's not been given any instructions other than to deliver food to her grandmother, so there's nothing "wrong" with stopping to chat with a talking wolf. While the wolf tricks her, she also tricks him. She uses her wits and saves herself with a humorous ruse: she tells the wolf she won't taste good, he should wait until she's relieved herself before he eats her. When he lets her go to the outhouse with a string tied around her ankle, she slips it off, ties it around a tree stump, and leaves the wolf to keep calling out, "Hey, are you done yet?"

Grandma dies, but granddaughter lives on. And there is no red hood.

The first written version, and the one which created the story's moralistic template is Charles Perrault's 1697, "Little Red Riding Hood." A tale about a capable young woman here becomes the story of a vain, spoiled, disobedient brat who gets what she deserves. It is Perrault who adds the iconic red hood, a gift from a doting grandmother to a "pretty child." The red hood has a double symbolism: the colour of scandal and blood, it suggests her sin and foreshadows her fate. And hood, or chaperon, already had the meaning in French, as it does in English today, of one who guards a girls' virtue.

Perrault's mother explicitly lectures her daughter to not stray from the path, not stop and look at flowers, not talk to strangers. Instead, she disobeys on all counts. She idles, gossips and is seduced by the sensuous delights of the forest, both flowers and wolf. For her transgressions she is punished with death. As if the plot were not explicit enough, Perrault adds a postscript spelling out that his is a story about what happens to girls who let young men take liberties:

"One sees here that pretty, well brought-up young girls should never listen to anyone who happens by, and if this occurs it is not so strange that a wolf should eat them. I say "wolf," but all wolves are not of the same kind. There are some who are pleasant and follow young ladies right into their homes, right into their beds." Orenstein points out that Perrault is playing on French slang for a girl's loss of virginity: elle avoit vû le loup---she’d seen the wolf.

Later, the Brothers Grimm publish a variation, "Little Red Cap," in 1812 with one important change. While Grandma still perishes, a fatherly woodsman both rescues Red and delivers a stern lecture: "a little maid should be afraid to do other than her mother told her." As Zipes writes, "Its quite evident the Riding Hood can be 'daddy's darling' only if she learns to toe the line."

With Perrault and the Brothers Grimm the "classic" plot is in place. Little Red Riding hood is vain, silly and helpless, to blame for her own "rape" and dependent on male authority for rescue.

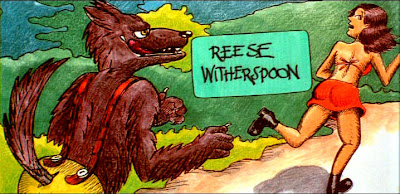

Freeway

The film we look at this week, Matthew Bright's Freeway, is a film which like Cat People both plays with and against multiple genre conventions. Like Cat People, Freeway is part horror film (it could even be said to essentially share the same monster---the werewolf). It also has, as several critics have pointed out, "one foot in the grind house and one in the art house." Director Bright himself labeled the film an "artsploitation" movie: marrying the over-the-top action, sex and violence of exploitation films with an astutely feminist re-telling of the fairy tale "Little Red Riding Hood."

For our purposes, we should look for the ways the film uses/subverts genre convention. Some things to think about while watching are the conventional relationship between the horror film monster and "his" victim, the usual "'punishment" of sexuality in horror/slasher films, the violence for violence's sake code of exploitation films, the handling of female characters in exploitation/splatter films, realistic vs. cartoon violence, and the many ways this film changes and even defies these "rules."

As even this cursory list implies, horror and exploitation films have a specific way of treating gender and sexuality---maybe one could go so far as to say that's what they're always really about at their red, bloody core. And more than just the iconic use of the colour red links these genres to the venerable fairytale/children's story, "Little Red Riding Hood." To examine Freeway's rewriting of that narrative, we first need to review the story as it develops from folk tale to children's story.

Friday, April 20, 2007

Small footnote on set design...

I've always been struck by the almost funny use of the painting in this scene from Cat People. This picture is only one of several cat-themed objects in her apartment, but it is a very expressive one since the crafty kitties eyeing the bird visually "rhymes" with Irena's own bird troubles. The look on their faces is priceless.

The painting is a reproduction of a famous portrait by Francisco Goya, Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuniga. I'd never actually looked it up, so I decided to when previewing the film for class.

The painting is a child's portrait and it features several birds besides the pet magpie the subject is playing with (by the way, the magpie is holding Goya's calling card in his beak). There is also a cage full of finches which provides an even stronger link to a piece of action in the film: Irena's accidental killing of her own pet, a caged canary.

But look at the group of cats in the corner. These are the ones featured in the framing of Irena in the shot. It looks to me like these cat's eyes have been reworked to brightly stand out from the dark canvas, and reshaped into more sinister expressions!

Cat People

Cat People is one of a trio of remarkable collaborations between director, Jacques Tourneur and producer Val Lewton. Cat People, I Walked With A Zombie, and The Leopard Man, were all low budget “horror” films made in the early 40’s at RKO. What distinguishes them from other films of that genre and budget is Tourneur’s ability to create highly atmospheric, noir-ish visuals that suggest more than they actually show. The scripts and plots Tourneur worked with were also extremely intelligent and creative. Cat People uses the trappings of a horror film to construct a metaphor for female sexual fears and repression. I Walked With A Zombie is an ambitious recasting of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre as a voo-doo inflected monster movie.

In his essay on Jacques Tourneur’s horror films, Ed Gonzalez points to another complex aspect of the Lewton/Tourneur thrillers that raises them above the usual ilk: “There's a certain multi-cultural conflict that distinguishes the Lewton-Tourneurs. In 1942's Cat People, the director's most famous film, the exotic Irena Dubrova (Simone Simon) embraces her cultural past as her sexual urges begin to overwhelm her. In 1943's superior I Walked With a Zombie, Betsey Connell (Frances Dee) similarly acknowledges the power of tradition inherent in Caribbean voodoo lore. In Leopard Man, resistance to tradition and authority and the desire for privilege kills the film's three Mexican women. These anti-racist conflicts seemingly pit a foreign culture against an American one, challenging cultural expectations.”

Tourneur later moved on to direct some of the most seminal of Hollywood film noirs such as Out of the Past and Berlin Express. I think as we look at Cat People this week, we might want to go back and review the previous blog post on film noir so we can talk about how the film both makes use of and subverts elements of the genre (I’m thinking in particular about how Cat People handles the status of the “bad” “dark” woman in a manner that runs explicitly counter to genre expectations).

Another genre concern is the horror film, and again we’ll want to pay attention to how Cat People both conforms to and breaks these conventions. The wikipedia discussion of the history of horror films covers the central elements of the genre: “In horror film plots, evil forces, events, or characters, sometimes of supernatural origin, intrude into the everyday world. Horror film characters include vampires, zombies, monsters, serial killers, and a range of other fear-inspiring characters.” In Cat People, the specific monster “pathology” is lycanthropy: the werewolf. Although Irena fears transforming into some kind of predatory big cat (like a leopard or a jaguar), the basic situation is the same---a human becoming something nonhuman, wild and deadly.

That Irena’s putative transformation is tied to her sexuality is one way the film’s subject links to film noir and its fear of female desire. Of course, Cat People gives us something much more complex than the male hysteria over vagina dentata that is a trademark of both noir and its literary companion, the hard-boiled detective story. Here, none of the men fear Irena, it is Irena herself that is afraid of sex.

Thursday, April 19, 2007

Advance Screening

I think the majority of students in this class have been doing very well. The jump in the level of engagement and ability between papers one and two, plus the continuing accumulation of interesting points of view in the logs has been extremely enjoyable and satisfying---to me, and I hope to you, too. That said, there are students who are still woefully behind, in terms of handing work in and in terms of even understanding what we’ve been doing in class. So this final paper offers something different to each group of students. For those who have truly been students, this paper should be seen as a challenging opportunity to present a polished example of what you’ve gained over the semester. For those who have been occupying seats in the classroom, this paper is a last chance to try to turn something in.

Choosing either Storytelling, Hamlet, Cat People, or Freeway, discuss how the film addresses the status of Truth. Pay particular attention to the relation between specific narrative elements and the film’s subject matter. In other words, how does the film uses the devices of film making (including genre) to raise questions about the nature of Truth?

Some things to consider. Both Storytelling and Hamlet focus on the narrative mediation of reality. Both of these films spend time examining, among other things, the crucial role that communication media play in our apprehension of the world and it’s “truth.” Storytelling juxtaposes the conceptual categories of “fiction” and “nonfiction,” as well as two different media: written and filmed narratives. And nearly every one of the characters represent conflicting and contradictory views or “truths.” Hamlet draws our eye, over and over again, to the dominance of the visual image in contemporary culture, and the privileged status of film as medium for understanding and expressing ourselves.

Cat People and Freeway both use what could be considered trivial or debased art forms (the horror film, melodrama, comic books and the exploitation film) for serious ends: a feminist critique of traditional notions of female sexuality. Cat People can be read as a study of female sexual repression and Freeway rewrites a fear-engendering blame-the-victim children’s tale (Little Red Riding Hood) into an over-the-top ode to female empowerment. In Cat People, Irena’s “truth” (her fears and desires) is dismissed by the other characters, especially the authority figure of the (male) psychoanalyst. In Freeway, Vanessa not only wards off an attack by a serial killer, but also repeated attacks on her honesty and truth telling.

We can talk a bit about this next class since Cat People only runs 71 minutes. We’ll see Freeway the week after that, with an all discussion class the following week to hash out anything else necessary for this paper. All papers must be turned in on the last day of class, when we’ll also be screening one final film yet to be announced.

Length: 6-7 pages, typed, double-spaced, titled and stapled

Due: May 15 (Final day of class)

Monday, April 16, 2007

Bardcore

Almereyda's remark about the existence of a Hamlet porno made me want to track down some evidence of it. Turns out there's not just one, but at least two Hamlet skin flicks as well as a whole slew of Shakespearian themed porn videos. Which makes sense, I guess, given the penchant for puns in porn titles. Who could resist Romeo In Juliet? The Taming of the Screw? Much Ado About Nuttin'?

Here's a humorous run-down of some of the titles in this sub-genre, including a synopsis of X Hamlet: "Something is pervy in the state of Denmark..."

A slightly more academic appraisal of the Bardcore genre can be found here.

Bits (mostly Hamlet) for this week's discussion...

I want to spend our discussion time this week not only on Hamlet and Storytelling, but also other narrative issues we've observed in the films and stories we've looked at thus far. I think this will help focus your thoughts for the final paper. However, at this point I'm not sure I will have the assignment for the final paper fully drafted---so our discussion may be more open ended than I would like. Either way, here are some things to read and think about:

To think more about Storytelling, I suggest you go through all the Student Logs which address this film. Some interesting points have been made in the comment threads---for example, just this morning one of Brittany's logs sparked some new ideas for me that I want to discuss further tomorrow night.

Since we didn't have much time to talk about Almereyda's Hamlet last class, I expect we will spend a lot of time with it. I'm bringing it to class again (also Storytelling) so we can look over some of the scenes and talk about the use of Shakespearian language in the film. The "problems" that students might have with this is soemthing I want to address:not to browbeat you all, but as a jumping off point for questions about language in general. Still, I do have to sneak one criticism in here: you need to read the play first, or at the very least read over the synopsis I provided you with. Although I've asked students to prepare for each of the film's we've screened (and provided much of the material for that preparation), this is one film where such preparation is crucial.

Here are some interesting essays and reviews of Almereyda's film. First, Elvis Mitchell's review in The New York Times, which begins: "It is curious; one never thinks of attaching Hamlet to any special locale," the critic Kenneth Tynan once wrote of Shakespeare's tragedy, and the director Michael Almereyda has brilliantly seized upon that by rooting his voluptuous and rewarding new adaptation of the play in today's Manhattan. The city's contradictions of beauty and squalor give the movie a sense of place -- it makes the best use of the Guggenheim Museum you'll ever see in a film -- and New York becomes a complex character in this vital and sharply intelligent film."

Mitchell highlights one of the things I want to talk more about: the overwhelming presence of New York City in the film. This is integral to the way Almereyda highlights the mediation of the visual image. As Alexandra Marshall points out, "Typical of their generation, Hamlet and Ophelia try to escape into the technologies of image making." And Marshall also links the emphasis on visual technology to the presentation of character in the film: "The characters in this Hamlet are conveyed--with the multiplicity of perspective that also marks our era--as an ensemble of complex personalities with layered and sometimes discomforting histories together."

The dominance of visual media and communication technology is also discussed in Cynthia Fuchs's article on the film: "Poor Hamlet is living in 21st-century Manhattan, where video and electronic surveillance is the norm: cameras find you on sidewalks, stores, offices, elevators. There's no place where you're not on screen, performing consciously or unconsciously for someone's leering and likely profit-minded benefit. "Reality TV" rules: The Real World, Making the Band, Letterman's hijacky street-interviews, Cops, and Big Brother. There are cameras everywhere."

As Fuchs points out, the camera is an instrument of domination, as well as representation---a point also made in Alan A. Stone's review, "...[Hamlet] enters the king’s court, now a corporate press conference, with a video device in each hand; facing down the world with his camera instead of his mordant wit. "

Fuchs also provides a detailed explication of Almereyda's staging of the infamous "to be or not to be" soliloquy in Blockbuster: "He's contemplating his limited options — suicide or homicide? — just as the shot cuts to the store's TV screen, where Eric Draven (Vincent Perez) contemplates one of his own vengeful murders in The Crow Part 2. This reference could not be more astute, not only because the movie features a pissed off dead guy assassinating his own killers, but because this sequel in particular — following Brandon Lee's terrible on-set death in the original Crow — is all about burdens, of history, consumption, and youthful angst, you know, exactly the issues troubling our boy Hamlet."

You can find Almereyda's own thoughts on the film here. A few excerpts: "I was hovering over various possibilities, relatively obscure plays -- and I was resisting Hamlet. It seemed too familiar, too obvious, and it's been filmed at least 43 times. Better to leave it to high school productions, spoofs and skits and The Lion King. As T. S. Eliot noted years back, Hamlet is like the Mona Lisa, something so overexposed you can hardly stand to look at it.

But masterpieces are definably masterpieces because they have a way of manifesting themselves in our everyday lives. The play, and the character, seemed to be chasing me around New York. I passed high school kids quoting Hamlet on the street. I was informed of the existence of a Hamlet porno film. And I found myself thinking back to my first impressions of the play, remembering its adolescence-primed impact and meaning for me -- the rampant parallels between the melancholy Dane and my many doomed and damaged heroes and imaginary friends: James Agee, Holden Caulfield, James Dean, Egon Schiele, Robert Johnson, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Jean Vigo.

...Through all this I was watching every version of Hamlet available in New York, scheduling systematic visits to the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Television and Radio and the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. (This is a curiously claustrophobic activity. You plug yourself into headphones and a monitor mounted within a tight Formica cubicle, surrounded almost exclusively by middle-aged men studying old Broadway musicals.)"

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

Interesting Work with Film

Above, two images from Nicolas Provost's Papillon d'amour, and a photo of Douglas Gordon's Between Darkness and Light (After William Blake).

Last night in class I briefly mentioned the work of artists who use existing films as the material of their work. I brought this up because I was talking about one of the ideas at play in Michael Almereyda's Hamlet: the absolute dominance of film (or more broadly, visual representation/communication media) in contemporary culture. While I want to write more about this in preparation for our discussion session next week, I thought I'd first give you a look at some innovative video art as food for thought.

You can see Nicholas Provost's beautiful Papillon d'amour on YouTube (low res, unfortunately) and read a bit about his work at the Video Data Bank. Papillon d'amour is made from footage of Akira Kurosawa's film Rashomon and I should probably say a bit about it here, too. I've mentioned Rashomon in class because of it's important status in film history and also its interesting handling of narrative structure: its nonlinearity and lack of closure. If you've never seen it, you can actually view the film online via the Internet Archive, a marvelous database of film/video/television images, most of them available in their entirety. Rashomon would fit quite well with the other films we've been looking at in this class, too, since as Stephen Prince points out in his essay for the Criterion Collection's release, "...the film has had a huge impact on modern culture. Rashomon is that rare film which has transcended its own status as film. Rashomon has entered the common parlance of everyday culture to symbolize general notions about the relativity of truth and the unreliability, the inevitable subjectivity, of memory [my emphasis]. In the legal realm, for example, lawyers and judges commonly speak of “the Rashomon effect” when first-hand witnesses of crime confront them with contradictory testimony."

I don't have any clips to show of you of Douglas Gordon's much bigger body of work, but here is a blog which has some interesting commentary on his recent show at MOMA, including 24 Hour Psycho, Between Darkness and Light (After William Blake), and Left is right and right is wrong and left is wrong and right is right, which splits Otto Preminger's Whirlpool into two panels which both mirror each other and consist of every other film frame.

The Guardian has an interesting discussion of Between Darkness and Light (After William Blake), as well as some photos and commentary on other of his work. From the article:

"[In] Darkness and Light (After William Blake)...two films run continuously, on either side of a translucent screen. On one side, Henry King's 1943 historical biopic Song of Bernadette, about Saint Bernadette, whose visions of the Virgin at Lourdes led to her sanctification and the founding of the pilgrimage site. On the other side of the screen runs The Exorcist, William Friedkin's 1973 horror movie of demonic possession. The images and sound from both movies meld and glide apart...There are inadvertent synchronicities between the two films: one is about virtue and goodness (and shot in black and white), the other unadulterated evil (shot in particularly seamy, grubby colour), but both are concerned with faith and doubt. The resulting "third image" is peculiar. The two films seem to haunt one another. Not only that, but the moments that collide so mysteriously are also always different, as the films are of different length and run continuously...heavenly visions juxtapose with evil infestations; the heavenly and the horrible keep crossing over, literally as well as figuratively."

Wednesday, April 4, 2007

Lost All My Mirth: Michael Almereyda's Hamlet

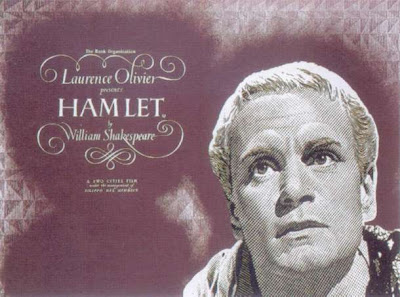

Above, some scenes from the film and director Almereyda on the set.

Michael Almereyda's Hamlet is the only film of a Shakespeare play that I like--that I think is not only good as an interpretation, but also good as a film. One reason for this is that this is a very self-reflexive piece of filmmaking. Besides being about the story of Hamlet, its also a film about the dominance of media, of visual culture, of communications technology in contemporary life. Almereyda manages to work in references to nearly every form of currently existing media. Video abounds; television screens and computer monitors, surveillance cameras and Times Square telescreens are included in nearly every shot. Some of the dialog is delivered via email, fax, teleprompter and answering machine; eavesdropping becomes wiretapping. And Hamlet wields a Pixelvision camera in the film's first extended sequence. As one critic remarked, "this is a Hamlet for the information age."

Almereyda has set his Hamlet in NYC year 2000 and slightly modified a few plot elements: Claudius is CEO of Denmark Corporation, fighting off a hostile corporate takeover by competitor Fortinbras. Elsinore is no longer a castle, but a swank hotel. Claudius and Gertrude make public appearances at press conferences and social benefits, not court.

Ophelia is a trust fund princess slumming on the LES, dressed in couture and sneakers and carting her cameras and photography equipment around in a Manhattan Portage messenger bag. Hamlet is a slacker film school student, a would be video artist obsessively reviewing footage of his life with the smudged door stamp from last night’s club still on the back of his hand. That we live in a world irrevocably mediated by the image is eloquently, wittily, and forcefully brought home by Almereyda's staging of that most iconic of all theatrical moments, Hamlet's "to be or not to be" soliloquy, in a Blockbuster video store.

The film also continually juxtaposes high and low culture elements on every level: the Shakespearian language we hear confronts the contemporary images we see, the soundtrack combines music referencing Hamlet by both classic composers (Tchaikovsky's "Hamlet") and rock musicians (Nick Cave and The Birthday Party's "Hamlet Pow, Pow, Pow"), even the casting carries this theme through by combining figures with pop culture resonance (Ethan Hawke, Julia Stiles and Bill Murray) with those more associated with theatre and Shakespeare (Sam Shepard, Diane Venora, Liev Schreiber).

The film is visually and aurally dense: there's much to look at and much to listen to. The score, by film composer Carter Burwell, is evocative and haunting. I uploaded it all to the Voxblog, Extra Things, if you want to listen to it.

So where can we most profitably place our eyes and ears?

While I think there is much to be said about how Almereyda treats Shakespeare's text, I don't know if that's the best place to begin for a class devoted to narrative. True, Almereyda cuts much, but frankly the last stage production I saw (Andrei Serban's referenced in my post below) ran about the same length of time. I like placing the famous speech from Act II at the beginning ("I have of late, where for I know not, lost all my mirth...") because it both cuts out the backstory blabla of the watchmen and it is my favorite bit in the play (though for me the best rendition of that speech in film remains Richard E. Grant's declamation in the final scene of Withnail & I).

Instead, I think we could begin with looking at the issue of mediation: the way our perception of the world, of how things are, is mediated by narrative and the various media in which it is encoded.

Above all, Almereyda's Hamlet argues for the primacy and power given film in contemporary society. That is why his film references so many forms of the reproduced image, and why he specifically locates the central elements of Shakespeare's play within an explicitly filmic context: Hamlet as aspiring filmmaker and avid film fan, the replacement of the play-within-a-play with a film-within-a-film, the Blockbuster location of "...to be or not to be...," and finally, Hamlet's questions about the reality of feelings emoted on the stage are now asked of a Movie Star, a pop culture icon of passion and action. "What would he do had he the motive and the cue for passion that I have?" asks this Hamlet, not of one of the court players, but of James Dean.

Quintessence of Dust: Hamlet Hell

I wanted to post some links to clips from different versions of Hamlet so students would have some points of comparison with Almereyda's film. I figured we were all familiar with various "classic" renditions, films like Kenneth Branagh's or the Franco Zefirelli/Mel Gibson version which attempt to mount a "faithful" recreation of what they seem to consider a sacred text. There are much more interesting routes to go when confronting the play T.S. Eliot referred to as, "the Mona Lisa of literature."

East German playwright Heiner Miller's, Hamletmachine, for example, is a kind of meta-theatrical commentary that uses the supposed "universality" of the play as an entry point for a far reaching critique of literature and politics. And Andrei Serban's 1999 staging was an attempt to capture not the just the play, but all the versions of it that have become dominant in collective memory.

So I took a brief look through YouTube and found a couple of things of possible interest. Here's a section from a typically "classic" staging, one which features Derek "I, Claudius" Jacobi as Hamlet and Patric "Jean-Luc Picard" Stewart as Claudius. And then there's The Simpson's version, which should be better, but does achieve a certain pathos in the casting of Chief Wiggam as Polonius and Ralph Wiggam as Laertes ("Look! Daddy's stomach is crying!!"). I also came across a clip from Tom Stoppard's film of his play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which is kind of nice to look at against the way the same scene is handled in Almereyda's film.

But mostly I found that YouTube is a bottomless pit of everybody's crappy video version of scenes from Hamlet staged for their high school English class. Each one of these imagines itself to be "hilarious" and "original," and yet I found 8 different "lego-mation" versions, at least 16 machinima (drawing from The Sims, Halo, World of Warcraft, Final Fantasy, and Second Life, among others), 22 Star Wars/Hamlet fusions and "gangsta" and rap Hamlets beyond count ("Homeboy Hamlet," "Hamlet in Da Hood," etc.). Apparently, if you give white suburban American teenagers a video camera the first thing they do is recreate some "jackass" stunts and then they move on to pretending they're both black and Shakesperian actors. I'll let you mine YouTube for "gems" yourselves.

You can also find some of the videos linked to here over on my VoxBlog, Extra Things, along with the one actually interesting thing I found on YouTube: Andrew Bellware's Hamlet short. I don't know anything about him or his production company, PandoraMachine, but the film was shot in Pixelvision, a "method" pioneered by Michael Almereyda in his first film, Another Girl, Another Planet, and something which has become almost a signature for him---you'll see bits shot on Pixelvision in Hamlet and I think all his other films as well.

Tuesday, April 3, 2007

Man delights not me: Shakespeare's Hamlet

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is probably the most famous play in the English language. One reason for its continued popularity is its seemingly “modern” rendering of individual psychology and motivation. Although there is plenty of onstage action, the play’s emphasis is really on internal battles: Hamlet’s struggle with himself, his indecisiveness and inability to act in ethically complicated situations make it an ideal text for multiple interpretations.

The following is a quick n’ dirty synopsis of the play’s plot. It should help with any major trouble you may have in reading the play. If you want a more detailed, act-by-act and scene-by-scene description you can look here, but I don’t think that will be necessary as Almereyda makes extensive cuts and revisions in the play.

Hamlet, the son of the King of Denmark, has come home to Castle Elsinore for his father’s funeral. Hamlet’s mother, Queen Gertrude, has married the former King’s brother, Claudius--who is now himself King. Hamlet is still mourning his father’s death and visibly disturbed and depressed over his mother’s remarriage. He doesn’t like Claudius and he’s acting weird around his girlfriend, Ophelia. Ophelia’s brother, Laertes, and father, the Lord Chamberlain Polonius, warn her that Hamlet might be only playing with her affections.

The neighboring kingdom of Norway (specifically Prince Fortinbras) is threatening to invade. One night, some watchmen see a ghost resembling King Hamlet. Hamlet and his closest friend Horatio talk to it and learn that his father was murdered by Claudius---by having poison poured in his ear. The ghost wants Hamlet to avenge him but he’s not entirely sure how best to get this revenge.

Claudius and Gertrude notice Hamlet’s increasing anti-social behavior (or madness) and they appoint two of his school mates, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on him. Claudius is worried that Hamlet suspects something. Polonius on the other hand, bumblingly thinks Hamlet is just moody and lovesick for Ophelia. He, too, spies on Hamlet and Ophelia to report back to Claudius. Hamlet breaks with Ophelia.

Hamlet decides to trick Claudius into betraying himself by staging a play which recreates the murder of King Hamlet. The play upsets Claudius, clinching Hamlet’s resolve, but when he goes to kill him, Claudius is in prayer and Hamlet cannot follow through. He then confronts his mother and hearing a noise behind her bedroom curtain, stabs at it, thinking it Claudius. He has, however, killed Polonius. Claudius sends him back to England, ostensibly for his own safety, but in reality he’s also sent Rosencrantz and Guildenstern with orders for his death.

Ophelia, already upset by Hamlet’s rebuff, now goes mad in grief at her father’s murder. She drowns, perhaps a suicide. Laertes, her brother and Polonius’s son, returns in a rage from France, demanding that Claudius punish Hamlet. Hamlet sends word that he’s returning, and realizing his plot didn’t work, Claudius hatches a new one with Laertes: to challenge Hamlet to a fencing match. Laertes will bring a poisoned blade; Claudius will provide a poisoned cup. During the match, Gertrude drinks from the poisoned cup instead and Laertes fatally wounds Hamlet, but is himself wounded with his own sword. As he dies, he tells Hamlet about Claudius’s plot and Hamlet kills Claudius. Hamlet dies begging his dear friend Horatio to tell the story. Fortinbras and his army enter the castle to begin a new regime.

Friday, March 23, 2007

Storytelling

Above, three images from the film we screen this week, Todd Solondz's Storytelling, including one featuring The Red Box.

I want to point out a few things for students to watch for and think about: the film's bifurcated structure and, of course, the infamous Red Box.

Storytelling is a diptych of sorts: it consists of two separate films, one titled "Fiction," and the other titled "Nonfiction." While the two sections share some implicit themes (like the in/interdeterminacy of the supposedly opposite categories of "fact" and "fiction") on the surface they seem unrelated and could stand alone as independent narratives. "Fiction" is the story of young student enrolled in a creative writing seminar, and "Nonfiction" relates the story of a would-be documentary filmmaker. Each of the main characters is in some sense committed to telling "the truth," but that turns out to be a less straightforward proposition than often assumed. Of interest to our class is how the film takes up autobiography and documentary in its double structure.

"The Red Box" is how director Solondz handled the problem of ratings and censorship, a problem specific to the United States but not elsewhere on the planet except, as he points out, "in places like Iraq and Iran." In the United States in order for films to get wide distribution they must be "voluntarily" submitted to the MPAA for a rating (voluntary in name only because of studio/distributor pressure to comply). Ratings have a direct effect on box office and thus on whether or not your film will ever get seen. The criteria used to determine ratings are obscure, arbitrary and often contradictory. The bottom line? Studios and distributors want to avoid a rating of "NC-17," which in 1990 replaced the "X," but still carries a stigma. (For a history of MPAA ratings and the struggles waged by various filmmakers, this wikipedia entry is a good place to start.)

When Solondz first presented Storytelling to the MPAA, he was told he would have to remove a sex scene between a white female and a black male in order to earn an R rating. But Solondz had covered himself in his contract as explained in this interview: "I had it in my contract that I had the ability to put boxes and beeps wherever necessary in order to procure the "R" rating; I feel the audience is entitled to know what they're not allowed to see. The alternative is to remove the shot, and this is something I found unacceptable. You only get the opportunity to see the red box in this country...I chose red because I didn't want it to be subtle...I needed a very strong color to pop out so there would be no ambiguity. It's not a mistake; it's right in your face: You're not allowed to see this in our country."

In a gesture worthy of Hester Prynne, Solondz not only chose the colour scarlet , but also made sure his signifier of sexual repression was obnoxiously large: The Red Box, as you can see above, stamps out more than just an actor's "naughty bits," it interrupts the narrative itself.

Hypertext

One of the written texts you might be using for your second essay is a hypertext work: Shelley Jackson's "My Body: A Wunderkammer." So this post is to help familiarize you a bit with some of the history of this digital format and its use as a creative medium.

Hypertext, the ability of html code to render online text with embedded links to other texts, images, or other kinds of data files, is ubiquitous throughout the internet. I don't know where you could look online and not be looking at some use of it. I'm sure everyone in class is by now used to seeing words and phrases highlighted in different colours that you "click" on to take you to somewhere else: a different web page, a definition of a term, an email address, and so on. Its pretty much what the internet was set up to do.

Hypertext was invented as a means to provide an easy interface for information retrieval, a way to organize and cross-reference both the knowledge of the past and the vast amounts of data being generated by digital technology itself. In short, a solution to the 20th Century problem of information overload. Any history of hypertext usually begins with reference to Vannevar Bush's prescient essay, "As We May Think," published in 1945. In it he imagines an electronic device he calls a "Memex." This "mechanized file and library" would be produced for individual use and take the form of a screen-topped desk and keyboard. Though Bush's "Memex" is not exactly like a PC hooked up to the internet, the basic idea---a means for individuals to have virtual access to a meta-archive---is there. That's why Bush's essay was the inspiration for the men generally credited with hypertext's invention, Ted Nelson and Douglas Engelbart.

What is interesting about Bush's predictions for later creative and artistic uses of hypertext and hypermedia are these comments that follow his criticism of the conventional ways information is indexed:

"The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Mankind cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but ... [t]he first idea, however, to be drawn from the analogy concerns selection. Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized. One cannot hope thus to equal the speed and flexibility with which the mind follows an associative trail, but it should be possible to beat the mind decisively in regard to the permanence and clarity of the items resurrected from storage."

Yes, that's right. The non-linear associative function of memory is here imagined as the ultimate organizing methodology for categorizing everything. This should give pause to those readers who still find the nonlinear "confusing," "annoying," or "stupid."

Because hypertext is a way of organizing material that attempts to overcome the inherent limitations of the linearity of traditional text its easy to see why it would be a medium that invited creative uses. As Heather pointed out in class, it changes things on a very fundamental level. The narrative experience, no matter what the structure or medium, has always been an experience of finite duration. The final page is turned, or the credits roll and the lights go up, and its over. Heather's very good question was, "How do you know when to stop?"

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Camera Eye: This American Life Clip

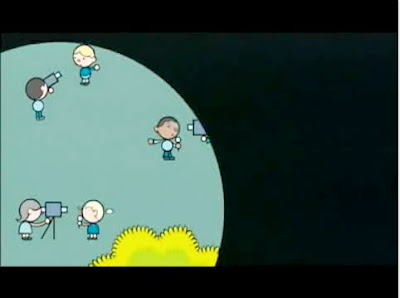

This is the animated short I mentioned in class last night. It's a segment from the new This American Life series on Showtime. I titled it "Camera Eye;" I don't know what it will be called when its broadcast.

It follows the typical format of a piece on the NPR radio program, This American Life: someone telling a "true story." In this case, the show's host, Ira Glass, is interviewing someone (Jeff) about a playground craze they remember from grade school. Their conversation is paired with an animation by the artist Chris Ware.

I thought it might have relevance for our class for several reasons. The story is about memory. The story is autobiographical and presented within the frame of a program that itself is a kind of documentary/autobiography hybrid. And, the story is about the mediation of "real life" by the camera: something with consequences even when the camera isn't real.

I'm also interested in the way that the audio narrative is supplemented with visual images too. The Showtime series marks the negotiation of This American Life between different media. Formerly, the fact that it was a radio program, a purely aural experience, was essential to the nature of the program. It was a narrative form grounded in talking and listening, not looking. How will the addition of visual elements change this?

In this segment we see one approach, one that doesn't pair the audio with filmed footage of the incident, but with an obviously artificial illustration---a cartoon drawn in simple geometric shapes.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

Special Sneak Preview

I'll hand this out in Tuesday's class and we'll discuss it there, but here it is now as a kind of "advance screening."

The first paper was a mostly descriptive exercise which asked students to pay attention to elements of film that they might usually overlook. Some were elements common to all narrative whatever medium: things like narrative structure, issues of closure, and point of view in general. Others were specific to film as a medium: things like editing, camera shots, visual construction of the character’s and viewer’s POV.

The point of the paper was to begin to see. Or perhaps to see differently by paying attention to something other than plot. To put it yet another way, to begin to see films as something constructed in particular ways and for particular reasons, rather than as slick finished products quickly consumed and quickly forgotten. That’s why I chose films that I hoped would stick in your throat, films that might not pass as easily through your brain as a cotton candy does through your digestive tract.

As several of you have pointed out in your logs, the four films that we’ve screened in class, Christopher Nolan’s Memento, Terence Davies’s Distant Voices/Still Lives, Chris Marker’s la Jetee and Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation all share a concern with the relation between identity and memory. It is this theme that is the focus of the second assignment, which also asks you to pair a film narrative with a written narrative in your analysis. You can choose to work on either of these pairs:

Memento, Christoper Nolan

"Memento Mori," Jonathan Nolan

or

Tarnation, Jonathan Caouette

"My Body: A Wonderkammer," Shelley Jackson

The first pair are two different treatments in two different media of the same plot "seed." The second pair are two autobiographies which stretch the boundaries of that form.

In this assignment you are basically working on the relation between form (which includes narrative structure, use of genre conventions, and specific medium) and content. Discuss the relation between each text's use of narrative/genre conventions and how it conceptualizes memory and identity. Also address the differences that the medium (film or written narrative) makes. What are some of the specific restrictions or advantages of each for dealing with issues of memory and identity?

Please remember to title and staple your paper.

Length: 5-6 pages, typed, double-spaced.

Due: Tuesday, April 10

Friday, March 16, 2007

Genre Part Three: Autobiography

Above, portraits of some of the writers discussed below: Saint Augustine, Jean-Jacques Rosseau, Frederick Douglass, William Wordsworth, Shelley Jackson.

The autobiography as we know it is a relatively recent literary invention. Although human beings have probably always recorded accounts of their lives---cave painting hand outlines could be read as primal form of autobiography---the term autobiography, as well as the idea of telling the story of your life for no other reason than to "express yourself," only appears in the Western tradition in the 18thC. And the main reason for this is that the modern idea of "the self" is a pretty modern concept, too.

Before you can imagine the autobiography, a certain idea of the self has to be in place: "self" as an independent entity important for its own sake. Thus, not only are the lives of the Famous and Powerful (biography) worth recording and reading, but anyone's life has the potential to disclose something worthwhile and meaningful to others. Broadly speaking, this only happens in Western European history with the birth of modern secular society. Liberating the self from a position of subordinance under God, Priests, the King, and so on, the modern notion of the self defines "the human" as something naturally free, autonomous, independent, governed by reason, and possessing a universal worth or dignity.

While some earlier written forms seem to correspond to the autobiography, works like Saint Augustine's Confessions (397) were created for other purposes than only to relate the details of a particular man's life. While Augustine does write a great deal about his circumstances, the point of his book is his eventual conversion to Christianity and its true subject is man's relation to God, not man himself.

One of the first "true" autobiographies is Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions (1782). His use of a title with religious associations was meant to signal a new form of "confession:" not a recital of spiritual sins but an examination of human subjectivity, an exegesis on how the self develops. In the Age of Enlightenment, the autobiography came to stand as the human document par excellance, the literary form which most celebrated that which was human and explained why such concepts as "human rights" and "human worth" should be at the center of political, philosophical and moral inquiry.

Its easy to see why the autobiography came to play such an important role in the 19thC struggle against slavery. In his famous work The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), former slave Douglass dares to stake his, and by extension all slaves, claim to humanity upon the very literary ground which was understood to define "the human." The very act of writing his autobiography demonstrated his possession of an independent and rational self with as much claim to human rights as any other.

One of the essential "human" elements of the autobiographical form is its close correspondence to the act of remembering---it is, after all nothing more than a collection of memories. The relationship between autobiography and memory is often part of the story told itself. William Wordsworth's long autobiographical poem, The Prelude (which he worked on for most of his adult life and was only published in 1850 after his death) is devoted to a series of ever deepening explorations of what he called "spots of time," moments that first appear to have no great significance but are in fact touchstones for intense memories:

There are in our existence spots of time,

Which with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating Virtue, whence,

... our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired;

...Such moments

Are scattered everywhere, taking their date

From our first childhood.

(Book XII, 208-225)

Wordsworth's "spots of time" are individual past experiences through which he can later discern his development as both a poet and a man, moments which come to have new and deeper meanings as he returns to them years later in memory (much like Terence Davies in Distant Voices/Still Lives).

While autobiography is conventionally thought of as a nonfiction literary form, as a narrative it betrays its status as something consciously crafted, designed and made. It is not synonymous with a person's actual life, it is an edited version of it. And since autobiographies are the stories of people's lives, they include the fictions that are part of those lives: dreams, memories, fears and beliefs.

An interesting autobiography to take a look at in relation to Tarnation might by the hypertext "My Body: A Wunderkammer," by Shelley Jackson. Digital hypertext is make up out of textual fragments or lexia that can be accessed by readers in various and random order. Hypertext's potential for expanding narrative modalities---exploding linearity----has made it an interesting medium for contemporary writers like Jackson who often make the material textuality of their work a significant factor in it (see for example, her ongoing project Skin, subtitled "a mortal work of art," which is a narrative being published one word at a time on the skin of 2095 volunteers, of which I am one).

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Genre Part Two: Documentary

Above are some images from the films, Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929), Titicut Follies (Frederick Wiseman, 1969), Harlan County, U.S.A. (Barbara Kopple, 1976) , The Thin Blue Line (Errol Morris, 1988) and the television program Trauma: Life in the ER (TLC 2006).

Documentary film refers in general to all nonfiction film practices, all attempts to visually record, or "document" reality. The conventional assumption is that documentary is "objective," devoid of any subjective bias of the filmmaker and merely a faithful reflection of the "truth" of reality. However, throughout its history, the question of how any form of representation necessarily shapes, rather than simply records, reality has been at the center of all documentary work.

Narrative is selection after all, editing is fundamental to the work of both filmmakers and writers. One of my favorite television programs is the "reality" show Trauma: Life in the ER on the The Learning Channel. A friend of mine works on it: she's a documentary film maker who supports herself as a freelance editor. When I told her how much I liked it, she scoffed, "I hate it! We have to sort through around 5000 hours of film every week and shape it into two or three story lines. By the time I get done its total fiction!"

The fact/fiction barrier is, I hope you are learning, a highly permeable membrane. I think that's one of the points of the short story, "We Kill What We Love," which the fire drill prevented us from talking about in our last discussion session, but which maybe we can remember to talk about in this Tuesday's class. The images above this post are taken from films which illustrate the range of documentary practices throughout film history.

The earliest moving pictures shown to public audiences were by default documentaries. They were single-shot moments captured on film: a train entering a station, a boat docking, an airplane taking off, or mundane scenes of daily life. They were devoted to the sheer novelty of showing moving images of an event. Travelogues, scarcely edited footage of travel to "exotic" locations were probably the next film "form" to emerge: again the emphasis was on the novelty of the technology and the novelty of the experience it could provide an audience.

Shaping film into a narrative, a fictional narrative, followed soon after and early fiction films themselves followed established narrative forms: filmed versions of Great Literature or film scripts which mimicked the narrative structure of plays and novels. That film might have its own narrative language, that as a medium it might offer a different narrative modality are the motivations behind the first real cinematic experimentors, working interestingly enough, on the documentary and nonfiction side of things.

Dziga Vertov, working in the Soviet Union in the 20's and 30's believed the camera, with its varied lenses, shot-counter shot editing, time-lapse, ability to slow motion, stop motion and fast-motion, could render reality more accurately than the human eye and thus produced documentaries that exploit cinematic technique. His films are quite different than the static "aim the camera at the world and walk away" style that is now conventionally associated with documentary film. They transcend the notion that the camera should be limited to merely reproducing the human line of vision (which still dominates all filmmaking, fiction and nonfiction, today) and instead try to capture a "reality" more truthful in its visual representation of multiple images and multiple points of view. For Vertov, the films of people like D. W. Griffith were merely "cliches, copies of copies, films overly indebted to novels and theatrical conventions." Instead, cinema must have " its own rhythm, one lifted from nowhere else, and we find it in the movements of things."

Filmmakers like Frederick Wiseman and Barbara Kopple represent another strand in the tradition: the documentary as visual journalism. Both filmmakers immersed themselves in the culture of the events they filmed. Kopple and her crew spent years with the families of the Kentucky miners whose struggles she filmed in Harlan County U.S.A. In making Titicut Follies, Wiseman spent years fighting powerful institutional and governmental restrictions: not only to get into the Bridgewater State Hospital to film the inmates in the first place, but then to be able to even show his film once it was finished.

These documentaries aim to take viewers as completely as possible into situations outside of the safety of mainstream middle america to reveal the (often government-sanctioned) violence and abuse that is also a part of american society (the shot from Harlan County USA is Kopple and her crew being shot---literally). The visual and narrative style of these documentaries favor the immediacy of the hand held moving camera, following the drama of a situation as it unfolds and historical back story told by utilizing images of newspaper clippings and other archival forms of research.

Errol Morris's The Thin Blue Line is interesting for the way that it combines interviewed testimony with clips of news media coverage and re-enactments of essential plot moments. It explores the true story of the arrest and convinction of Randall Adams for the murder of a Dallas policeman in 1976 and the evidence and argument that it makes eventually led to the overturning of Adam's sentence and his release from prison. In many ways Morris pioneered what has become the dominant look and feel of nonfiction filmmaking, something we see in countless "reality" television programs and recent documentaries like those of Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock.

I think one way to begin to think about Tarnation is in light of the entire tradition of documentary, one in which the mediated, or consciously crafted status of the image has long been under consideration.

(for some clips from some of the things discussed here, check my Vox blog Extra Things.)

We might also think about autobiography itself as a genre, but my thoughts on that will have to come in a separate post.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)