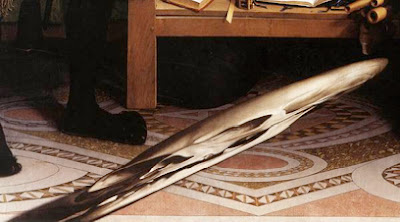

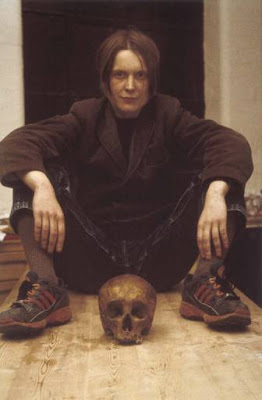

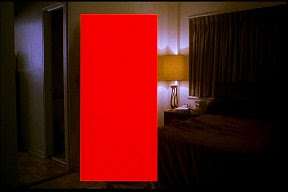

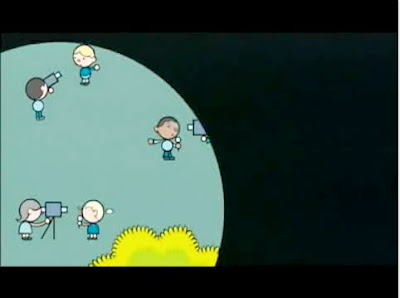

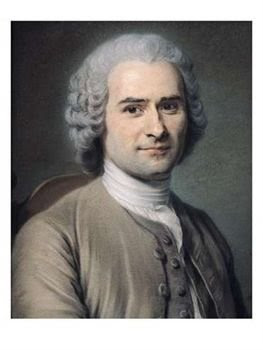

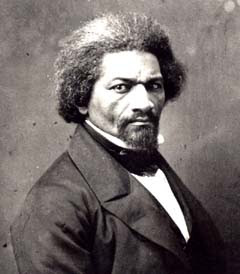

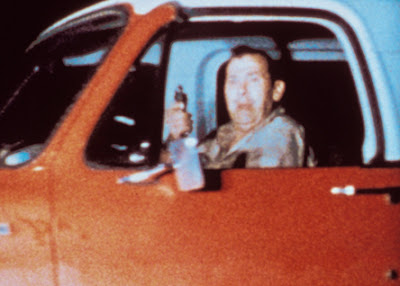

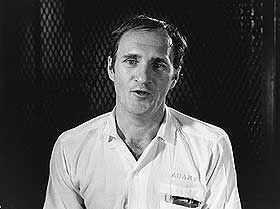

Above, three images from the film we screen this week, Todd Solondz's Storytelling, including one featuring The Red Box.

I want to point out a few things for students to watch for and think about: the film's bifurcated structure and, of course, the infamous Red Box.

Storytelling is a diptych of sorts: it consists of two separate films, one titled "Fiction," and the other titled "Nonfiction." While the two sections share some implicit themes (like the in/interdeterminacy of the supposedly opposite categories of "fact" and "fiction") on the surface they seem unrelated and could stand alone as independent narratives. "Fiction" is the story of young student enrolled in a creative writing seminar, and "Nonfiction" relates the story of a would-be documentary filmmaker. Each of the main characters is in some sense committed to telling "the truth," but that turns out to be a less straightforward proposition than often assumed. Of interest to our class is how the film takes up autobiography and documentary in its double structure.

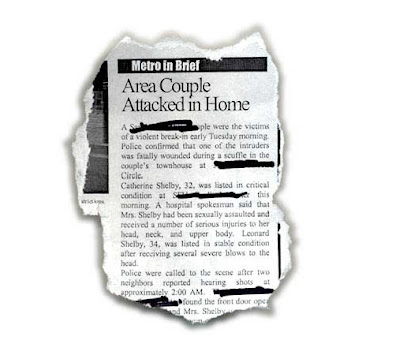

"The Red Box" is how director Solondz handled the problem of ratings and censorship, a problem specific to the United States but not elsewhere on the planet except, as he points out, "in places like Iraq and Iran." In the United States in order for films to get wide distribution they must be "voluntarily" submitted to the MPAA for a rating (voluntary in name only because of studio/distributor pressure to comply). Ratings have a direct effect on box office and thus on whether or not your film will ever get seen. The criteria used to determine ratings are obscure, arbitrary and often contradictory. The bottom line? Studios and distributors want to avoid a rating of "NC-17," which in 1990 replaced the "X," but still carries a stigma. (For a history of MPAA ratings and the struggles waged by various filmmakers, this wikipedia entry is a good place to start.)

When Solondz first presented Storytelling to the MPAA, he was told he would have to remove a sex scene between a white female and a black male in order to earn an R rating. But Solondz had covered himself in his contract as explained in this interview: "I had it in my contract that I had the ability to put boxes and beeps wherever necessary in order to procure the "R" rating; I feel the audience is entitled to know what they're not allowed to see. The alternative is to remove the shot, and this is something I found unacceptable. You only get the opportunity to see the red box in this country...I chose red because I didn't want it to be subtle...I needed a very strong color to pop out so there would be no ambiguity. It's not a mistake; it's right in your face: You're not allowed to see this in our country."

In a gesture worthy of Hester Prynne, Solondz not only chose the colour scarlet , but also made sure his signifier of sexual repression was obnoxiously large: The Red Box, as you can see above, stamps out more than just an actor's "naughty bits," it interrupts the narrative itself.

_01.jpg)

_04.jpg)